Killings by Ugandan military and police during joint operations in Kasese, western Uganda on November 26-27, 2016, warrant an independent, impartial fact-finding mission with international expertise, Human Rights Watch said today. On the bloodiest day, scores of people, including children, were killed during a military assault on the palace compound of the region’s cultural institution.

Police spokespeople reported the death toll over the two days as 87, including 16 police. Human Rights Watch found the actual number to be much higher – at least 55 people, including at least 14 police, killed on November 26, and more than 100, including at least 15 children, during the attack on the palace compound on November 27.

The government has arrested and charged more than 180 people, including the cultural institution’s king, known as the Omusinga, with murder, treason, and terrorism, among other charges. None of the 180 are members of the police or military and no one has been charged for the killing of the civilians, including children.

“The assault on the palace in Kasese, which killed more people than any single event since the height of the war in Northern Uganda over a decade ago, should not be swept under the carpet,” said Maria Burnett, associate Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “People in Kasese are still looking for their family members, including children, and they deserve answers and justice for these gruesome killings.”

In a telephone interview on February 24, 2017, Uganda’s military spokesman, Brig. Richard Karemire, told Human Rights Watch that there has been no investigation into the military’s conduct and that none is planned. The government is under an obligation to investigate any operation where there is such loss of life and should do so promptly. But given limited prospects for a credible follow up by domestic authorities, an independent, impartial investigation, with international expertise, should be urgently conducted, Human Rights Watch said.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 95 people in six subcounties of the Kasese district, including many families of the people killed, and reviewed video and photographs of the events. Many people voiced significant fears of reprisals given the presence of security forces in the area.

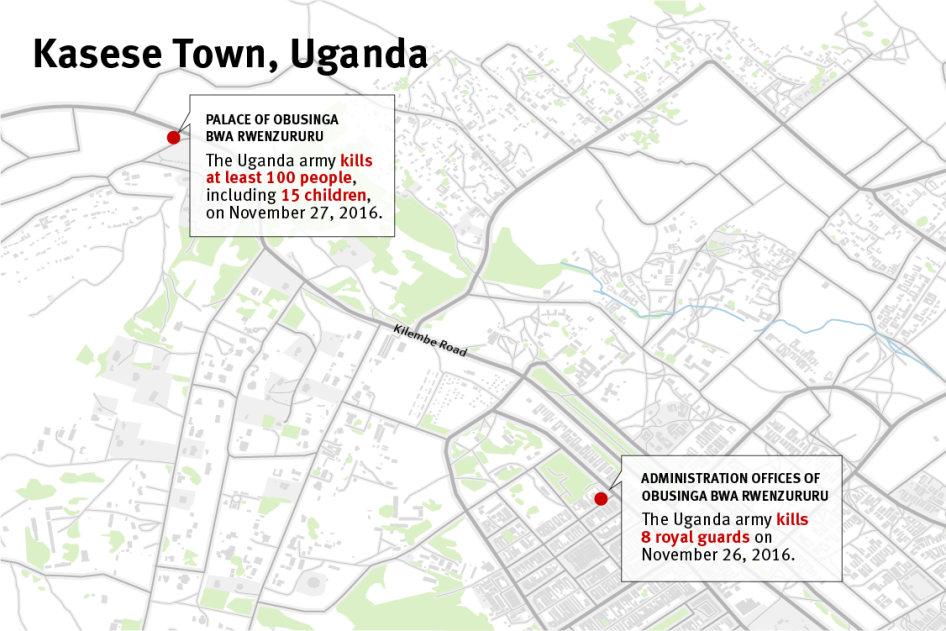

The violence began on the morning of November 26 in Kasese, where there has been longstanding tension between a local cultural kingdom and the central government. Soldiers, under the command of then-Brig.Peter Elwelu, forced their way into the kingdom’s administration offices in Kasese town. The soldiers killed eight members of the volunteer royal guards, who traditionally safeguard cultural sites. Many often carry agricultural tools, such as machetes, but are not formally armed by the kingdom or the government, and would not constitute an armed force or group under international humanitarian law.

Witnesses said that the killings prompted widespread concern among those loyal to the king, and word spread quickly to outlying subcounties that the kingdom was under attack. That afternoon, civilians, including some royal guards, attacked six small police posts far outside town with machetes. In the ensuing violence, at least 14 police constables and one crime preventer were hacked to death and security forces shot 32 civilians. Most of the alleged attackers were killed in the clashes.

The killings of police are a tragedy and families should continue to receive compensation, Human Rights Watch said.

By the evening of November 26, soldiers and police had surrounded the king’s compound in Kasese. On any given day, the palace could have hundreds of people inside, royal guards as well as women, children, and young people, cooking meals, learning vocational skills, and tending to the kingdom’s animals, among other tasks. Several people told Human Rights Watch that they received calls from family members inside the compound saying that the military would not let them leave.

The palace remained surrounded the next day. Witnesses said they saw then-Brigadier Elwelu and the police operations director, Asuman Mugenyi, in command over security forces, at Kasese police headquarters and the palace compound. Several politicians entered the palace that morning to negotiate. Eventually, the police took the king into custody and left with him.

At about 1 p.m., the security forces attacked the compound, using what witnesses described as an anti-riot vehicle to storm the gate, and shooting guns and then later rocket-propelled grenades. Many people said they heard loud explosions, and saw thatch roofs on the perimeter and inside the compound catch fire and be burned to the ground.

“About 20 armed men took up positions and started fire everywhere,” one survivor said. “Anyone who survived pled for their lives.”

In video footage reviewed by Human Rights Watch, two soldiers are seen beating shirtless male detainees who are lying on the ground with their hands tied behind their backs after running out of the burning palace compound.

The army has disparaged accounts that security forces used unnecessary lethal force over the two days, contending that those killed were armed fighters. But without independent investigations, its version of events raises more questions than answers, particularly regarding the actual death toll and why there was no effort to remove unarmed people and children from the compound.

Many families said they are still looking for the victims’ bodies but are afraid to ask questions about the attack or where the bodies are. “We buried [our brother] quickly, but because of all the threats, we still don’t know where his child’s body is,” one man said. “He was just 5 years old.” Human Rights Watch spoke to 14 families missing 15 children between ages 3 and 14 who were last seen in the palace compound on November 27.

Human Rights Watch found evidence, including accounts by confidential sources and medical personnel who witnessed the events, that security officials had misrepresented the number of people killed and eliminated evidence of the children’s deaths.

Human Rights Watch spoke to several army officers who expressed significant discomfort with the events in Kasese but were unsurprised by the absence of investigations into the military’s conduct. They said they did not believe that any local entity would have the space or independence to conduct a meaningful investigation without obstructions from the government and fear of reprisals. “It was a horrible event, but who in this country can investigate?” said one high-ranking military official. “It is far above us all. How do you wake up and start investigating so far above you?”

In the media, Elwelu, now a major general, has actively defended his decision to attack the palace, contending that the people inside were all armed fighters, including Congolese fighters, and saying that he now sleeps well at night. He has been promoted to chief of land forces, one of the highest-ranking positions in the army.

Ensuring independent investigations into the conduct of security forces would not absolve civilians who committed crimes from facing justice, but would ensure security forces are also held responsible for their conduct and demonstrate a fundamental commitment to rule of law, Human Rights Watch said.

The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials require law enforcement officials, including military units, to apply nonviolent means before resorting to force, to use force only in proportion to the seriousness of the offense, and to use lethal force only when strictly unavoidable to protect life. The principles also provide that governments shall ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offense under their law.

The Ugandan government should immediately suspend the commanding army and police officials believed to be most responsible for the killings and other abuses committed during the November violence, Human Rights Watch said. The government should promptly investigate, prosecute, and punish those responsible in accordance with international standards. The government should protect witnesses and compensate the families of victims.

Given Major General Elwelu’s command responsibility for the palace attack, he should be removed from command pending a full investigation, and should not participate in any internationally-supported training, conferences or joint exercises until investigations conclude. The government should acknowledge a more accurate death toll and facilitate the exhumation, identification, and return to family members of all the bodies disposed of by police and military in any location, guaranteeing the families’ safety.

Uganda has a primary obligation to investigate and prosecute the perpetrators of these killings, but thus far has shown no willingness to do so. Given the scale of the abuses and killings including children, as well as Uganda’s failure to commit to investigations, there should be an independent, impartial investigation with international expertise into the human rights violations associated with the November violence in Kasese, and any findings should be made public, Human Rights Watch said.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child should also undertake a joint investigative mission to Uganda and support a broader independent and impartial investigation.

Uganda’s international partners should maintain a strong demand for accountability, including support for an independent and impartial investigation with international experts. If given unfettered access to witnesses and forensic evidence, independent experts with a fact-finding mission could determine if the massacre on November 27 should be characterized as a crime against humanity.

“The horrific events of November in Kasese warrant international scrutiny in an independent, impartial investigation that can determine all the crimes that took place, including potential crimes against humanity,” Burnett said. “The victims’ families deserve answers about why the military and police killed the people in the palace, including young children.”

For details about the Human Rights Watch findings, please see below.

Longstanding Tensions in Kasese

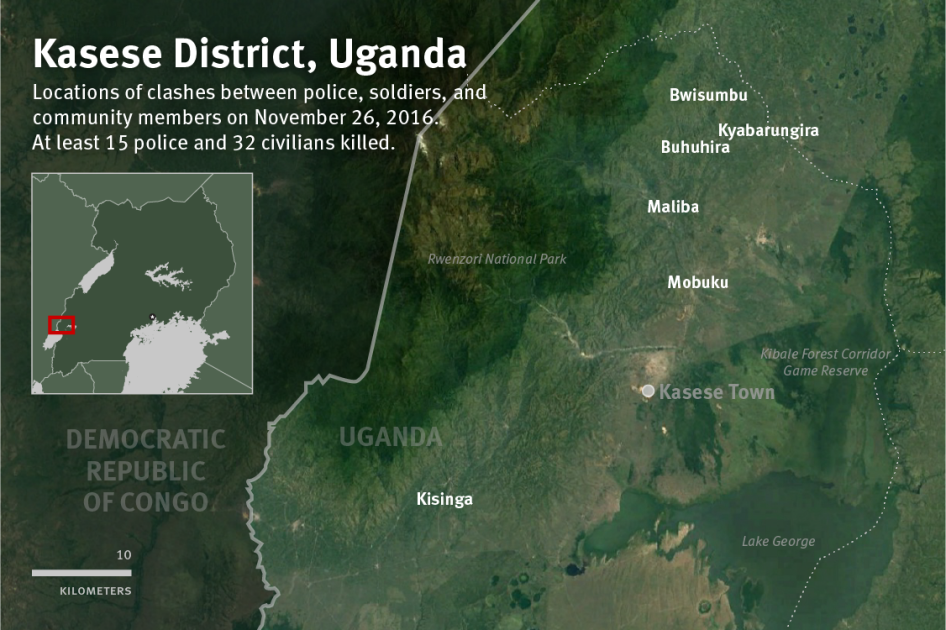

Human Rights Watch carried out research in Kasese district in Kasese town council as well as Rukoki, Maliba, Bwisumbu, Kisinga, Bugoye, and Bwera subcounties in January and February, 2017, interviewing more than 95 people, including over 30 families of those killed. Interviewees were located via multiple diverse local sources, including church leaders, local government officials, journalists, and activists. Many expressed significant fears of reprisals given the ongoing presence of security forces in the district.

There have been long-standing tensions, unresolved grievances and episodic violence between the government and the ethnic Bakonzo people of the Rwenzururu kingdom, headquartered in Kasese district. The role of cultural royalty in Uganda has been the source of debate historically and remains controversial. President Milton Obote outlawed all cultural royals in 1966, but President Yoweri Museveni permitted them to return in 1995, allegedly to win political support. In October 2009, President Museveni formally recognized the Kingdom of Rwenzururu, known locally as the Obusinga Bwa Rwenzuruuru and Charles Wesley Mumbere became the Omusinga, or king.

The 1995 constitution bars these “cultural leaders” from partisan politics, but they wield influence over their communities, particularly during elections. Opposition politicians have increasingly won elections in Kasese in recent years, at least in part due to historical grievances of ethnic marginalization.

Over the past three years, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly raised serious concerns regarding security forces’ use of lethal force during law enforcement operations in the region, the lack of credible investigations into the violence, and adhoc amnesties by the government for people arrested in these episodes. In July 2014, at least 92 people were killed and the government granted amnesty to more than 500 people. Between April and July 2016, Human Rights Watch found at least 13 of 50 people killed in operations in the Kasese subregion were unarmed and posed no imminent lethal threat to security forces. There has been little or no investigation of the conduct of government forces in these violent episodes or into the arrests of hundreds of civilians, some of whom have faced trial and convictions before military courts.

In the months leading up to the November killings, the government said it was trying to break up an alleged armed movement in the region, known as Kirumiramutima (the Strong-Hearted), which it contends includes at least to some extent, members of the royal guards in the service of the Omusinga. Royal guards themselves are not an armed force and do not constitute an armed group under international humanitarian law. In late November, the army invited journalists to visit alleged camps of the armed movement that the military had raided in Kabarole district, north of Kasese, leading allegedly to the killing of at least 10 royal guards. The president then issued a directive for royal guards to surrender and be disbanded, the army spokesman said.

Several families of royal guards told Human Rights Watch that in the days before November 27, they received phone calls saying they should come to the Omusinga’s palace compound to receive a possible package in exchange for disbanding.

Attack on the Kingdom Administration Offices

On November 25, the army, driving armed personal vehicles and supported by police, began patrolling Kasese. Community members were puzzled about the heavy deployment but some speculated that it was linked to the recent raids in Kabarole. On the morning of November 26, soldiers circled the area of the kingdom’s administration offices on Alexander Street, going around the block several times, witnesses said. The royal guards who routinely guard that office and the kingdom’s flag carry machetes.

Human Rights Watch was unable to find evidence that royal guards threw an improvised explosive device at the passing soldiers, contrary to claims by government spokespeople. Rather, multiple witnesses said that in mid-morning, soldiers ordered shopkeepers to close their businesses and demanded access to the kingdom offices. Royal guards closed the doors and refused them entry. No official kingdom representative was present.

Gunfire began shortly thereafter. People heard soldiers yelling “Come out!” in Kiswahili. The military shot live ammunition inside and outside the office. The soldiers eventually used ladders to scale the walls, pierced the roof and fatally shot those inside. Eight royal guards, two of them women, were killed, and soldiers removed computers and documents, numerous witnesses said. One person who carried the bodies said the bodies had bullet wounds to the head and back. The army did not reply to inquiries about casualties among the soldiers that day, but witnesses said they saw one soldier with a machete wound on his arm.

The army then went to neighboring shops, ordering shopkeepers to open their doors to see whether any royal guards were hiding inside, and stealing money and sodas. Later, the bodies of the royal guards were carried out of the office and police constables washed the blood out into the street.

Serious questions remain about the conduct of the military and police on Alexander Street that morning, from the failure of police to seek a warrant to search the office and potentially impound documents and computers, if there was a legitimate law enforcement objective, to the use of lethal force leading to so many deaths. The UN Principles on the Use of Force require law enforcement officials, including military units, to apply nonviolent means before resorting to force, to use force only in proportion to the seriousness of the offense, and to use lethal force only when strictly unavoidable to protect life.

Violence in the Subcounties

In the afternoon of November 26, at least 14 police, one crime preventer, and 32 civilians died in clashes around six small police posts, all several kilometers from Kasese town. Human Rights Watch spoke to the families of both police and civilians who died, but the motivation for the attacks remains unclear. Several families of civilians, including some royal guards who allegedly attacked the police posts, said that they had received phone calls informing them that the government was attacking the kingdom in Kasese town and that soldiers had killed royal guards.

The two deadliest clashes occurred in Bwisumbu and Kisinga subcounties, near Kagando hospital. In Bwisumbu, approximately 35 kilometers north of Kasese, civilians carrying machetes allegedly attacked the police post, killing three police constables and the crime preventer. Police, armed with guns, killed 30 people, including some who were not involved in the attacks, according to witnesses. Both witnesses and local government officials said that all the police who were killed died from machete wounds and had run out of bullets for their own guns. All the civilians died from gunshots.

In Kisinga town council, approximately 35 kilometers southwest of Kasese, a small group of civilians, including royal guards, allegedly attacked the police post near Kagando hospital carrying machetes, eventually killing at least five policemen and burning a police vehicle. One witness said that a royal guard pursued a policeman, managed to take his gun, and shot him. Soldiers came to reinforce the post, and later allegedly killed at least two assailants, including one who had been previously wounded and was attempting to receive medical treatment.

The Palace Attack and the Death Toll

Numerous media accounts and people who spoke to Human Rights Watch indicate that the military escalated its presence around the palace compound in Kasese town on the evening of November 26. Over the same period, some families of royal guards received phone calls from alleged kingdom officials asking them to come to the compound to receive packages in return for the disbanding of the guards. The media reported that on the morning of November 27, Elwelu gave the king an ultimatum, to disband his guards and remain with only nine. As he told the media days later, “We were supposed to storm that camp, that palace, by 11.” Eventually, the king was given two more hours.

It is not clear how many royal guards were inside the palace compound in total on November 27, given that guards are volunteers and work when they can. Families who lost loved ones in the compound denied Elwelu’s assertions to the media that everyone in the palace compound were “armed fighters.” The families said the dead and missing included young children and many others who worked for the Omusinga, learned vocational skills, or ran small businesses inside.

Some families of the king’s employees lived just next to or inside the compound in thatch-roof houses. Many of them were shot and killed or burned as roofing went up in flames in the afternoon assault, in part because the military appears to have prevented them from leaving the compound the night before.

“My husband was a farmer and not a royal guard,” one woman said. “On [November 26], he went to collect our daughter who was learning tailoring in the palace. When he arrived there, he called and said soldiers wouldn’t let him leave. I never saw my husband or my daughter again.”

Negotiations continued between officials of the kingdom and security officials over the disbandment of the royal guards. Some royal guards interviewed said they had been there awaiting packages in return for disbanding and transportation to leave the compound. Others said they had been confused about why they were being asked to surrender, and disassociated themselves from people who killed police the day before, saying they had been trying to undermine the kingdom.

Based on media reports, photographic and video evidence, and witness accounts, at about 1p.m. on November 27, the military stormed the compound, shooting inside with bullets and rocket-propelled grenades. Some people raised their hands to surrender, and security forces tied their hands behind their backs at the elbow, later shooting several. Photographs of what appeared to be dead bodies, some of men with their hands tied behind their backs, circulated on social media on November 27.

The thatch-roof huts in the compound, where children often would have gathered, caught fire and the video footage reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows several large fires raging in the compound. While no children’s bodies were brought to the Kasese mortuary, according to witnesses, some of the adult bodies there had significant burns. Some observers who entered in the palace in the days after the attack noted children’s items, including small toys, in the debris.

After a sustained period of shooting, the military and police – drawn largely from the Field Force Unit – arrested some people. Others had managed to flee out the back of the compound and up into the hills. In video footage reviewed by Human Rights Watch, some soldiers can be seen seriously beating people, with their arms tied behind their backs lying on the ground, outside the palace compound.

The army spokesman later was quoted in the media as saying that royal guards threw a petrol bomb and two soldiers were injured in the palace compound, but the army has not yet publicly said that any soldiers were killed in the palace that day. The spokesman said that “bombs and some of the guns that had been taken by the royal guards from the slain policemen in several places the previous day were recovered from the palace.” While there is no doubt that royal guards carry machetes and possibly had other weapons in the palace, it is virtually impossible that the weapons would have been the same as those carried by slain police officers from the subcounties. Given that military had surrounded the palace the day before the assault, royal guards would have had to kill police in the subcounty, then travel up to 35 kilometers, most likely on foot, and successfully smuggle firearms into the palace, directly past military and police deployments.

Precise details of what happened during the attack remain unclear, particularly to what extent any compound occupants posed an imminent lethal threat to anyone, largely because most people who survived are in jail, but the massive death toll of civilians raises significant questions about the use of lethal force. Human Rights Watch did not attempt to interview those in jail, or anyone charged with crimes for the November violence in Kasese, for fear of possible reprisals against them.

Weeks later in his bail application, the Omusinga wrote, “…my kingdom’s regalia, the parliament, traditional huts, coronation house and priceless cultural items at my palace including records were destroyed, burnt and or looted during the invasion during which several of my subjects were blatantly, ruthlessly and callously massacred after stripping them, tying their hands behind their backs and executed including women, children, royal palace domestic workers by a combined force of the UPDF [Uganda people’s Defence Force] and police.”

The military spokesman and General Elwelu have been quoted in the media aggressively contending that the November 26-27 killings were justified. Elwelu told the New Visionnewspaper on January 29, “Whatever happened in Kasese, it was the fault of the political leadership there…. It became a legitimate military target because it had become a command post for all that was happening in Rwenzori…What is important is the end result.” He said that the force used was not disproportionate, but rather the “minimum.”

His comments show a fundamental lack of understanding of international principles on the use of force, particularly the requirement that lethal force be used only when strictly unavoidable to protect life, Human Rights Watch said. As the principles state, “Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury… and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives.” Both Uganda’s army and police have received ample training in the use of non-lethal measures but appear to have made no effort to use those options on November 27. The presence of knives, machetes or a rifle inside the compound, as the military displayed to the media after the assault, is not evidence that lethal force was warranted.

“For all those people who died of bullets, only the government had the guns,” one resident said. “They had the capacity to avoid these killings. If there were wrong elements, they could have used other means, not just storming the palace and shooting everyone.”

The inclusion of international expertise in an independent investigation into the use of force would significantly contribute to understanding in more detail what transpired, whether the context of the massacre on November 27 is such that it could be characterized as a crime against humanity, and could lead to justice for victims from both sides of the violence.

Victims of the Palace Attack and the Search for Bodies

The government did not permit anyone to claim bodies until at least four days later, when identification was very difficult because the corpses were distended. At least 56 bodies were taken to the mortuary in Kasese, but bodies were also taken to Fort Portal in the north, Mubende to the east, and allegedly dumped in other locations, according to witnesses.

Just before the attack, a woman who ran a hair salon inside the palace compound had called a family member, terrified that the compound was surrounded by soldiers and begged him to come collect her and her 4-year-old child. Two hours later, her phone was off and he never heard from her again. He has looked in the mortuaries and checked the court case records, but found no trace of her. “We tried to ask the police about her,” he said. “There is no other step to do. If you ask too much, they can arrest you. We don’t know where to begin.”

Many people voiced considerable concern over missing children. Human Rights Watch was able to identify 15 children from 14 families who remain unaccounted for and all were last seen in the palace compound. One man whose brother and nephew have never been found after the palace attack said: “I went to the morgue, but there were no children’s bodies. Some say they were dumped in the forest but we don’t know. You cannot go to the authorities to seek information here. You cannot talk about these issues here.”

A woman whose husband and son had been inside said: “We are suffering, absolutely suffering. My children ask every day about their father and their young brother. Sometimes we just sit down with the family and mourn and cry. I am so desperate. The government did the biggest offense they could do in my life. My husband and child were more important than anything.”

The ultimate death toll from the two days remains difficult to determine. This is in part because government spokespeople have stated different numbers reflecting varying time periods, bodies have been taken to different morgues and mortuaries throughout the subregion, families remain fearful to report missing people, and ongoing allegations that some bodies, particularly the children, were dumped in an area where bush fires have flared in recent weeks.

Police spokespeople reported the death toll over the two days as 87, including 16 police who were all killed on November 26. The recently released US government human rights report on Uganda stated that media reports of the Kasese killings varied between 60 and 250 people over the two days. Based on available information Human Rights Watch believes that the total is at least 156 but is mostly likely higher.

Many of the bodies of civilians killed in the subcounties were not brought to any morgue or mortuary, but rather buried locally by their families. The mortuary in Kasese at one point had 96 bodies awaiting identification that week, including at least 40 bodies that had been initially brought to Fort Portal regional referral hospital. One man who was found alive in the piles of rotting corpses in the mortuary but he was shot dead by police upon his discovery, according to multiple witnesses.

All the police constables were identified and their bodies returned to their families. Forty-four bodies in Kasese were claimed by families but ultimately allegedly 52 unclaimed bodies were buried in individual graves on land near the military barracks, presided over by religious leaders. Confidential sources informed Human Rights Watch that police had taken DNA samples from the bodies but local families have no information about how to access that information to potentially identify missing people.

The Criminal Proceedings

While no military or police have been formally interrogated or charged with crimes as a result of the two days of violence, at least 180 people are facing charges of murder, treason and terrorism, among other crimes. At their first hearing on December 12, journalists observed significant untreated wounds on several of the defendants. As one noted, “[s]ome bore festering wounds on their limbs, which attracted flies.” The magistrate ordered an investigation into the treatment of the defendants, which remains pending. Security officials involved in the arrest, detention, and interrogation of these suspects should be questioned and face possible criminal charges under Uganda’s Prevention and Prohibition of Torture Act, Human Rights Watch said. Uganda passed the law in 2012, but no member of the police or army has been convicted under the act, despite ongoing allegations of torture throughout the country.

The defendants were at one point detained in Nalufenya police post in Jinja, eastern Uganda, over 400 kilometers from Kasese, most often used to detain terrorism suspects. Human Rights Watch and others have previously documented instances of serious mistreatment and torture in Nalufenya.

At least one royal guard died in Bombo military hospital, near Kampala, allegedly because of insufficiently rapid treatment of his injuries sustained during the palace attack. According to the military spokesman, at least 17 royal guards received treatment at Bombo but Human Rights Watch could not independently verify that information.

Obstructions

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly underscored the importance of averting future conflict by ensuring an independent examination of violence in the Rwenzori subregion. But even media reporting and commemorations have faced government obstruction since November. The government has made concerted efforts to prevent independent investigations of the November violence and to block access to information about what occurred.

Numerous people who spoke to Human Rights Watch voiced significant fear of reprisals, including possible arrest, for speaking about what they witnessed in Kasese on November 26 and 27. Security officials, particularly police from the Criminal Investigations Department and from the Flying Squad, a violent crimes unit notorious for mistreatment of suspects, have allegedly been seeking the whereabouts of those with first-hand accounts of what transpired and in some instances, threatening them with possible detention.

On the day of the palace attack, police arrested a prominent journalist, Joy Doreen Biira, and four others, charged them on November 28 with “abetting terrorism,” then released them. Police allege that they did not have permission to photograph some events during the violence, and confiscated photographs, video, and equipment. The charges remain pending. Biira’s arrest prompted other journalists to shy away from reporting from Kasese, other than on the official comments of the security forces. The government version of the events has heavily dominated the media since November.

Police blocked an inter-religious prayer for the victims that was scheduled for December 5 in Kampala, contending that under Uganda’s Public Order Management Act, the police leadership needed to give permission for the event. Human Rights Watch along with other human rights organizations contend that the law violates rights to free assembly by granting the police leadership overly broad and discretionary powers to regulate and prevent gatherings.

The Ugandan military has also threatened people who tried to talk about what they saw that day in Kasese. The former military spokesman, Paddy Ankunda, wrote in theDaily Monitor newspaper, “We…sound a strong warning that UPDF will not hesitate to initiate legal proceedings against any individual or group that continues peddling falsehoods and tarnishing the good image of the institution for the sake of gaining cheap political capital.” At no time did he encourage anyone with concerns for the conduct of soldiers or those looking for loved ones during the attacks to share their testimony with military investigators.

On December 1, the speaker of parliament agreed to add five new members to a committee that had been established months earlier, in the wake of post-electoral violence in the Rwenzori subregion, and add the November violence to their mandate. The committee, drawn largely from the parliamentary committee on defense and international affairs, began its work on December 7 but its inquiries quickly stopped and the chairperson told the media there would be no parliamentary report about the violence.

The media reported that the committee dropped investigations because government officials said that it could not proceed because the killings in Kasese are sub-judice (pending in a court). Given there are no court cases involving allegations of crimes committed by soldiers or police pending, there is no reason to obstruct such investigations, Human Rights Watch said. The Committee’s chairperson, a former police officer recently elected to parliament, has never reported back to parliament.

The Uganda Human Rights Commission issued a statement urging all sides to adhere to Uganda’s laws, but made no specific call to the military and police to investigate their forces’ conduct. The Commission has said it is carrying out investigations and will eventually issue a report.

Local and International Condemnation

At the time of the killings, there were multiple calls for investigations into the security forces’ conduct by local and international entities. The Buganda kingdom, another Ugandan cultural institution that had its own political tensions with the central government that led to police and military killing at least 48 civilians in September 2009, called for investigations into Kasese in a Christmas message. The kingdom urged the government to “do everything in its power to investigate and punish all those involved in the mass killings.” The Uganda Law Society called for a commission of inquiry consisting of both sides of the conflict.

On December 16, the European Union heads of mission issued a statement calling on the government to conduct an investigation in a “timely, inclusive and transparent manner, according to due process and the rule of law” and to make findings public. The US Ambassador also called for a transparent investigation via her Twitter account on December 10.

The Ugandan army is a close partner of the US, UK, and EU for training and joint military exercises as well as ongoing operations in the Central African Republic and Somalia. General Elwelu previously served in a leadership role in both those operations. The blatant lack of regard for the protection of civilian life and basic standards on the use of legitimate force, as well as obstruction of investigations into the military’s conduct, should raise serious questions about sustained cooperation with the Ugandan army, especially in light of his new role as commander of land forces, Human Rights Watch said.

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at Submit an Article