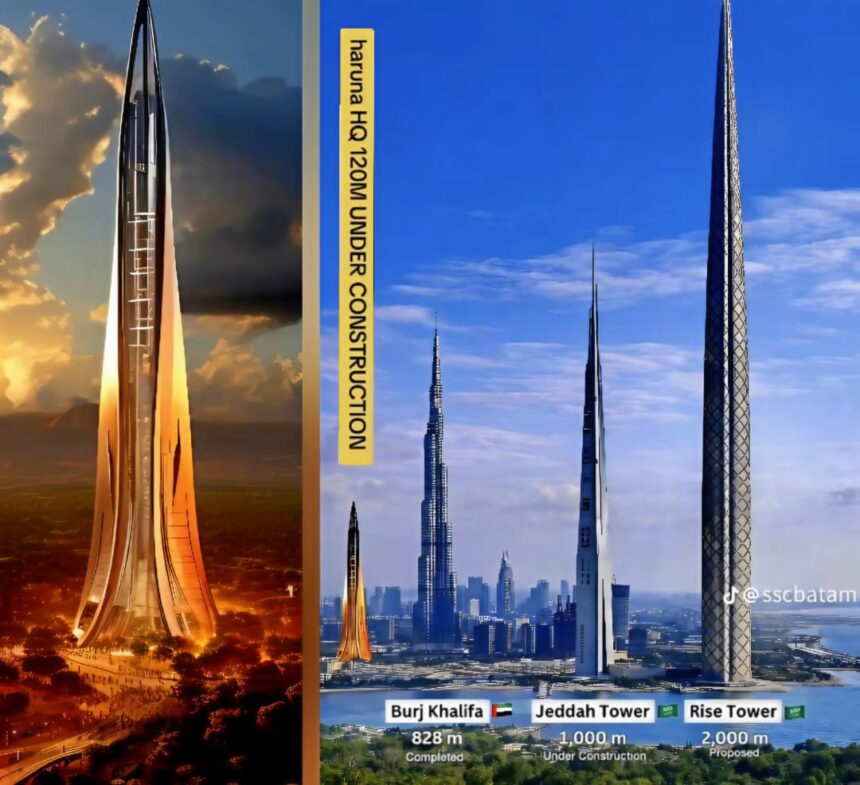

Kampala, Uganda — In the bustling heart of Nakasero, where commercial ambition meets Kampala’s historic skyline, a new property is poised to redefine Uganda’s vertical ambitions. Haruna Towers Nakasero, projected to rise to approximately 120 metres across 16 floors, could soon become one of the tallest private developments in the nation — a structure that signals Kampala’s entry into the global discourse on urban height and architectural ambition.

With floor slabs measuring six to seven metres and beams lifted up to two metres to accommodate advanced structural services, the design prioritises both flexibility and presence. For Kampala, where mid-rise offices and trading arcades have long defined the cityscape, the tower represents more than height: it is a psychological and economic benchmark, a statement that Uganda’s capital is thinking beyond its historical horizontal growth.

By contrast, East African neighbours have long embraced verticality. Nairobi’s Britam Tower (200 metres) and the Global Trade Centre Office Tower (184 metres) in Upper Hill and Westlands, respectively, signal Kenya’s mature high-rise culture. Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Lagos offer other regional points of reference.

Haruna Towers Nakasero, though not a supertall by international standards, stakes a claim within this regional ecosystem, offering a domestic threshold that could recalibrate Kampala’s urban economics.

Globally, the skyscraper conversation is dominated by iconic giants: Dubai’s Burj Khalifa (828 metres), Singapore’s Guoco Tower (290 metres), Hong Kong’s ICC (484 metres), Jakarta’s Autograph Tower (382 metres), and Bangkok’s MahaNakhon (314 metres). Haruna Towers does not seek to compete in absolute terms; its significance lies in proportion, contextual ambition, and the signaling effect on investor confidence.

Structural considerations for a 120-metre tower are substantial. Increased slab heights allow for mezzanine floors, high-volume retail, improved natural light, and flexible office layouts. Lateral stability systems, deep foundations, and high-efficiency vertical transport must align with Kampala’s wind patterns and soil conditions. Fire safety, mechanical ventilation, and circulation planning become central to successful execution.

Economically, the tower responds to real pressures. Land scarcity in prime Nakasero encourages maximisation of floor space and clustering of commercial activities. Uganda’s medium-term macroeconomic outlook, supported by oil development, infrastructure expansion, and a resilient services sector, creates an enabling environment. Urban migration trends in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area further justify vertical densification.

While market risk exists — including potential under-occupancy of commercial floors — Haruna Towers’ symbolic height could influence neighbouring land values and attract phased investment, similar to threshold buildings elsewhere in Africa and Asia. The tower could become a catalyst for Kampala’s first true high-rise cluster, anchoring a commercial identity that merges local context with international aspiration.

Haruna Towers Nakasero thus represents a delicate balance: ambitious but proportionate, regional yet globally aware, symbolic yet economically grounded. For Kampala, the 120-metre proposal is more than concrete and steel; it is a declaration that Uganda is ready to participate assertively in East Africa’s vertical discourse, signaling to investors, developers, and architects that the city’s skyline — and its ambitions — are rising.

As the plans advance, the world will watch whether Kampala’s tallest private tower becomes an isolated landmark or the first step in a new era of architectural ambition for Uganda’s capital.

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at Submit an Article