By Andrew Baba Buluba

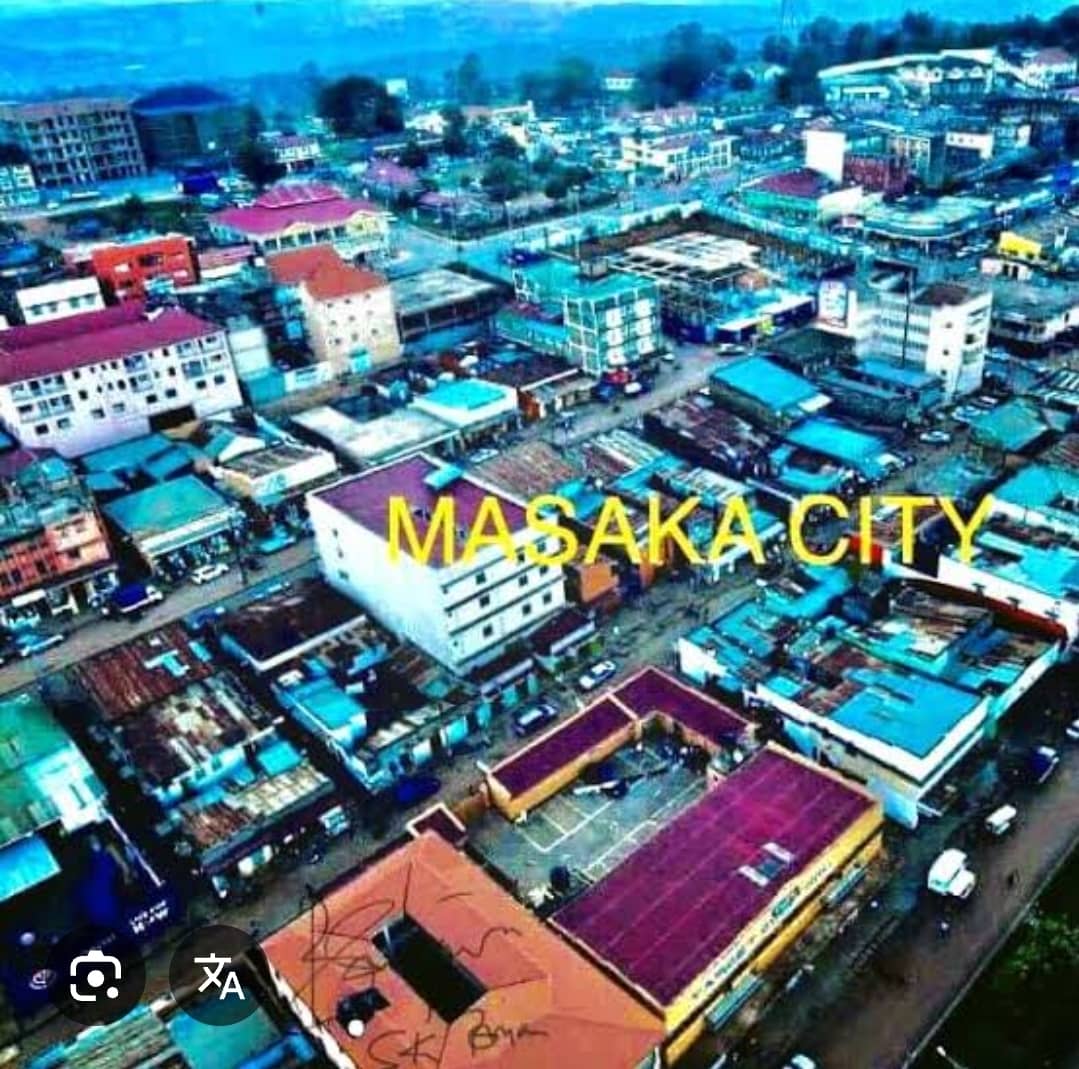

When I first came to Greater Masaka upon my appointment and posting as Assistant Resident District Commissioner ( A- RDC) in Rakai District, I knew I knew I was on a long course to learn new things about this beautiful pearl called Uganda. On the way to the remote District in Kooki, Masaka City acted as the main gate to this land of Kamuswaga. Rakai is a wonderful place, save for the scaring stories of cannibalism which I strongly refute as untrue. Two months into my work in Rakai, I had started scribbling some notes as I prepared to put the amazing story of this amazing kingdom of Kooki into writing. Then came my transfer to Masaka City. In Masaka, I learned that the history of the most part of Greater Masaka was intertwined. You couldn’t tell the story of Masaka City while omitting Kyotera, or Kalungu or Ssembabule. Thus, there was a story, and a very crucial one, to tell about this subregion, especially on how impressively they managed to bounce back from the ruins of war into the thriving business and commercial hub that Masaka City represents today. Hence the birth of this book : NRM And Greater Masaka’s Post Amin War Restoration.

CHAPTER ONE

From Ashes to Action: The Rebirth of Masaka (1979–1986)

When Idi Amin fled Uganda in 1979, Masaka City stood in ruins. What had once been a vibrant center of trade and culture was now a ghost of war—its streets cracked with shell-fire, buildings stripped of life, and families displaced or hiding in fear. The war may have ended, but its aftermath was no less devastating. It ushered in a period of prolonged uncertainty and silence—a time when leadership came and went, but progress stood still.

The Era of Instability

In the years following Amin’s ousting, Uganda entered a cycle of leadership changes that deepened the paralysis in regions like Greater Masaka. Between 1979 and 1986, four governments—led respectively by Yusuf Lule, Godfrey Binaisa, the Military Commission, and Tito Okello—held power briefly but failed to create meaningful recovery frameworks. Each regime appeared more focused on political infighting than the healing of a battered nation.

While Kampala remained the center of these transitions, Masaka was largely forgotten. Public infrastructure eroded. Schools, if still standing, lacked teachers and supplies. Hospitals operated without medicine or reliable staff. Roads decayed into channels of isolation, cutting off communities from economic and social life.

Amid all this, the people of Masaka showed incredible resilience. Local councils, faith institutions, and elders stepped into the vacuum, offering structure in the absence of state leadership. But these grassroots efforts, though commendable, could not rebuild a region fractured so deeply.

The Rigged Election of 1980

Hope flickered briefly in December 1980, when Uganda held its first general elections since Amin’s departure. That hope quickly turned to outrage. The Uganda People’s Congress (UPC), led by former president Milton Obote, was controversially declared winner of the election—despite strong belief that the Democratic Party (DP) under Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere had legitimately won.

Yoweri Museveni, then head of the Uganda Patriotic Movement and a candidate in the election, rejected the results outright. Though he placed third, Museveni viewed the UPC government as illegitimate and a continuation of Uganda’s cycle of authoritarianism and misrule. In response, he took to the bush—and history turned.

Seeds of Revolution

Museveni launched an armed rebellion through the newly formed National Resistance Army (NRA). He was soon joined by other movements, including Yusuf Lule’s Uganda Freedom Fighters (UFF) and Andrew Kayiira’s Uganda Freedom Movement (UFM), each bringing fighters, ideology, and spirit to the cause.

Their mission was clear: restore dignity to Uganda through a disciplined, people-centered revolution. For Masaka, this rebellion marked not just a political shift, but the beginning of rebirth—a delayed but determined awakening.

The Arrival of the NRM in 1986

When the NRA took power in January 1986 and ushered in the National Resistance Movement (NRM), Uganda began to breathe again. In Masaka, the change was immediate and tangible. Security forces stabilized the region, eliminating threats and allowing families to return safely to their homes.

Law and order were reestablished. Local councils regained authority. Traditional leaders were consulted and elevated. People who had long lived on the fringes of broken systems were finally invited into the architecture of governance.

Rebuilding with the People

The NRM government didn’t rebuild Masaka from a distance—it did so alongside its people. Public meetings, or barazas, were held to understand community needs. Youth were organized into service brigades to help reconstruct public spaces. Women were mobilized to participate in health campaigns, school initiatives, and income-generating programs.

Trust, long eroded by broken promises, began to regrow. The state was no longer an abstract force—it was present, responsive, and willing to listen.

New Foundations: Health, Education, Roads

Restoration was not just about political rhetoric—it manifested in real, life-changing ways:

– Health centers reopened. Medicines and trained staff returned. Immunization programs revived.

– Schools were rehabilitated, teachers reinstated, and new learning materials distributed. The introduction of Universal Primary Education paved a new future for Masaka’s children.

– Roads connecting Masaka to Kampala were repaired, catalyzing trade, mobility, and access to opportunity.

– Agricultural extension services reached farmers, providing seeds, tools, and training that helped revive Masaka’s economy.

A New Chapter Begins

The years between 1979 and 1986 were a bridge—from devastation to determination. They tested the endurance of Masaka’s people and revealed the consequences of leadership that overlooks the grassroots. But with the arrival of the NRM, the region began its real restoration—brick by brick, policy by policy, story by story.

In the pages that follow, I will explore the transformation of Masaka across key sectors—health, education, agriculture, governance—and share the testimonies of citizens whose lives reflect the region’s profound journey from ashes to action.

The NRM’s restoration of Masaka went beyond policy—it hinged on empowering ordinary citizens to reclaim ownership of their communities. This marked a radical departure from past regimes, where decisions were imposed from above, often with little regard for local realities.

Resistance Councils (RCs): A New Democratic Fabric

One of the NRM’s most transformative innovations was the establishment of Resistance Councils—grassroots governance structures that became the backbone of post-war civic life.

– Local Empowerment: RCs gave every village and town a voice in governance. Citizens no longer waited passively for officials from Kampala; they made decisions about sanitation, education, dispute resolution, and security in real time.

– Leadership Development: Many future national leaders began in RCs, learning accountability and community-building at the village level.

– Bridge Between Government & People: RCs served as conduits for government programs, ensuring public services reached even remote corners of Masaka.

– Evolution into Local Councils (LCs): As stability increased, RCs transitioned into the Local Council system still used today, institutionalizing civic participation.

This structure brought dignity to local governance—it proved that restoring a nation was not just the work of presidents and ministers, but of farmers, teachers, mothers, and youth.

The Muchakamuchaka Program: Security through Unity

In tandem with political empowerment, the NRM introduced muchakamuchaka, a basic military training program aimed at strengthening community self-defense and fostering discipline.

– National Unity Through Physical Training: Conducted in every region, including Masaka, adults of all backgrounds engaged in drills, political education, and fitness routines—instilling a collective sense of patriotism.

– Psychological Empowerment: For communities long traumatized by violence and abandonment, the training helped replace fear with preparedness.

– Rebel Deterrence: Muchakamuchaka created a vigilant citizenry capable of reporting suspicious activity and standing firm against potential rebel incursions.

Though some saw the program as unconventional, it became a symbol of civic awakening—a declaration that ordinary Ugandans would never again be passive victims of war.

The significance of Masaka to the NRA Liberation Story

In his memoir Sowing the Mustard Seed, Museveni described the strategic importance of Masaka and its surrounding areas, noting that “Masaka was a gateway to the south and a corridor to the west. Whoever controlled it could control the pulse of the rebellion.”

During a Liberation Day speech, he emphasized, “The people of Masaka gave us shelter, food, and intelligence. Without their support, the war would have dragged on much longer.”

President Museveni also praised the siege of Masaka (1985) as a turning point:

“When Masaka fell, the road to Kampala opened. It was the moment we knew victory was within reach.”

Stories from Fellow Fighters

– Gen. Elly Tumwine, who fired the first bullet at Kabamba, once said: “Masaka was where we tested our resolve. The siege taught us discipline, patience, and the power of unity.”

– Brig. Fred Mwesigye, one of the original 27 NRA fighters, recalled:

“The people of Masaka were not just spectators—they were participants. They hid us, fed us, and even joined us.”

– Andrew Lutaaya, a key logistics figure, helped transport fighters and weapons through Masaka’s terrain. His role was critical in the Kabamba attack and later operations in the region.

Masaka’s Strategic Role

-The siege of Masaka (Sept–Dec 1985) was one of the longest and most decisive battles of the war. The NRA’s victory there led to the capture of Kampala just weeks later. The region’s road networks, coffee trade, and proximity to the southwest made it a logistical hub for the NRA. Local support was overwhelming—villagers provided food, shelter, and even recruits, including women.

The writer is the Assistant Resident City Commissioner for Nyendo Mukungwe- Masaka City

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at Submit an Article